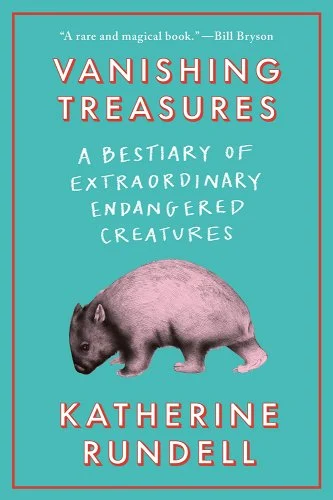

Katherine Rundell’s follow-up to 2023’s Impossible Creatures—a novel that sees two children trying to protect “the world’s last magical place,” which is home to all manner of mythical being—goes hand in hand with its predecessor. But rather than a children’s fantasy story, Vanishing Treasures is a nonfiction survey of some of the seemingly impossible creatures who have and do call our planet home. As the title suggests, many of our brilliant neighbors are disappearing at an alarming rate. This is mostly, it turns out, due to humanity’s overwhelming superstition, greed, and desire to dominate whatever is beautiful and rare.

From wombats to golden moles, each chapter belongs to a different animal and is introduced with a lovely illustration by Talya Baldwin of the creature in question. Rundell combines history, personal anecdote, and narrative flair to instill in her readers the senselessness of certain human acts as well as the importance of preservation. Sometimes humanity’s cruelty is born of actual need, as in the case of the Parisian famine of 1870—the result of a Prussian blockade—which led ultimately to the sale and slaughter of two male elephants: brothers, Pollux and Castor. At this time, the common Parisian was eating rats and cats to avoid starvation. Meanwhile, the luxury grocer who purchased the pachyderm siblings from the zoo did so with a mind to get as much money for each slice of them as possible from the city’s wealthiest residents. In this chapter, as she does throughout, Rundell juxtaposes the description of the animals’ demise with the revelation of their extraordinary abilities. Pollux and Castor’s trunks for example, “the tenderest part” of them, which were “sold as a delicacy for forty francs a pound,” possess 40,000 muscles compared to the 650 of an entire human body, and are both precise enough to “pluck a single blade of grass” as well as strong enough to “lift 350 kilos, or swing a man into the air.”

Rundell’s own observations and interactions color her depictions of each animal in ways that are easy to latch onto. Every clever description is as enjoyable to read as the facts. The stork, she describes as “a stroke of calligraphy by a flamboyant and ambitious god,” and the Marabou specifically “with its tufts of hair and big neck pouch hanging like a scarf or a testicle has the aspect of a disreputable undertaker.” The tendency to humanize other species is often decried, and not unjustly, as every living being should indeed be accepted on its own terms. However, it is also true that our understanding of the world around us is based on the individual lens of lived experience. Rundell’s style of description does a great deal to bring these astounding beings with whom we share a world, if not a life, within the realms of human understanding and empathy.

The wonders presented in this book are many; among them, the ceremony and intimacy with which other species interact. The dancing of seahorse couples, the careful designation of new homes for hermit crabs who have outgrown their old ones, the system of punishment and reward meted out by crows all showcase that every living being is so much more like us than we deign to recognize—no doubt because doing so would make it that much harder to use and destroy them for our own ridiculous reasons. Like Civil War surgeon Burt Green Wilder who, in 1863, trapped a golden orb spider and collected 150 yards of its silk with the ultimate intention of “making a gown for his lady love,” an enterprise he “abandoned only when he calculated that it would take five thousand spiders.” Or back in the 1700s when “bear grease” was touted as a cure for baldness, and the hearts and eyes of bats were thought to make one invisible. Or even now, when the giant bluefin tuna is in a state of rapid depletion despite most people’s inability to taste the difference between it and a yellowfin. The contents of this book amaze and infuriate in equal measure, an effective combination. It is fury that tends to spur us into action.

The final chapter of this book is on humans, as wondrous a treasure as any found in this book. In our chapter, Rundell tells the story of the Sibylline books—nine volumes of Greek poetry that held great wisdom about our world, and how much (or how little) those who had the chance to possess this wisdom valued it. Vanishing Treasures contains wisdom about lives that deserve our full attention and protection, invaluable not least because, as little as we know about them now, once they are gone—like so many species already lost—it will be impossible to bring them, or the opportunity to learn about them, back from extinction.

NONFICTION

by Katherine Rundell

Doubleday Books

Published on November 12, 2024

Gianni Washington has a Ph.D. in Creative Writing from The University of Surrey. Her writing can be found in L'Esprit Literary Review, West Trade Review, on Litromagazine.com, and in the horror anthology Brief Grislys, among other places. Her debut collection of short fiction, Flowers from the Void, is out now with Serpent's Tail (UK) and CLASH Books (US).