It’s rare to encounter a writer with the range of Sarah Gerard. Last year, she put out the slinky, chaotic, and cat-forward chapbook The Butter House; before that, the darkly comic New York City novel True Love, with the kind of quick dialogue that can give you paper cuts. And now, we have Carrie Carolyn Coco, a painstakingly investigated collective memoir of Carolyn Bush’s life and of her death.

The book begins with the night that Carolyn was murdered at age twenty-five by her roommate, Render Stetson-Shanahan, who’d gone to Bard College at the same time she did. A new friend to Carolyn at the time of her murder, Gerard set out to create with this book a container that might hold both the author’s investigation of the crime and, perhaps more importantly, the stories Carolyn’s close friends and family wanted to tell about her. Gerard does not shy away from taking to task the powerful media and academic forces, which—in small moves that added up to a huge sum—undercut Carolyn after her death. And Gerard balances this necessary focus on Carolyn’s death with a palpable commitment to telling Carolyn’s life story and giving her back agency on the page.

Sarah and I sat down with her dog on a Tuesday to talk through her process and aims.

This conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

Afton Montgomery

There are two places in the book where you directly address what this text is and state your purpose. One is early, in the chapter “Grieving Giver Riven River.” You write, “I wanted to know why it happened,” and “more importantly, I wanted to know Carolyn. We had only just begun to form a friendship . . . I feared the stories [of her] would be lost.”

And then at almost the exact halfway point of the book, you write, “I wanted to create an archive of the stories people were sharing and find more of them and gather them all into an indelible record of her impact.” You told Carolyn’s friend Pamela Tinnen, “I want to tell her life story.”

The first feels like an internal statement on what you, Sarah, wanted from the book. The second feels like an external one: this is what the book will be in the world. I got caught on this “an indelible record of her impact” because it’s right at the midpoint, which I think of as the crease that tells a reader how to fold the story in their mind, how to make sense of it. Will you talk about “record of impact” as a genre and how it might be different than true crime?

Sarah Gerard

I know so many people who knew Carolyn. At the start of this project, I was really grieving for them, and wanted to give them voice and grieve with them. Carolyn and I had a brief friendship, briefer than I wanted it to be, certainly, but we also had this interesting shared past in Florida, and so many of our friendships were overlapping that I felt like it was strange that we didn’t know each other better before she died. I wanted to spend time with those people and keep her alive for as long as possible, and tell a story about their grief, rather than tell the story about only what happened to her.

Although, I thought that was also an important thing to examine as well, as a symptom of systemic violence that female-presenting people live with in our society.

I also had a sense that, in telling Carolyn’s story, I would be able to understand why this happened. If I could tell her life story and learn more about the person who murdered her, and what his story was, I could figure out how their lives overlapped and why she died the way she did. I think that turned out to be pretty true.

She died before she could self-actualize. I thought that was so tragic. She was on an upward trajectory. She was so bright. She was doing so many important things for the community. She was working through school, she had aspirations. But I didn’t want the fact that she wasn’t able to self-actualize to be the story. You know, she really did impact so many people. I saw it firsthand; she continues to do that.

Afton Montgomery

The idea of cataloging her impact is so interesting because within the context of this book there’s no way for me not to think of an impact statement. And that is so different than a crime itself.

Sarah Gerard

Victimology is a very important part of crime that is not talked about enough. Carolyn wasn’t the only victim. Carolyn was the main victim, and her story is obviously more important than anyone else’s here, but she wasn’t the only one harmed. I wanted to focus on the victims. Render’s biography doesn’t come in until late in the book, on purpose. If we were going to talk about Render, I wanted that to be through the lens of the people who knew Carolyn. Like when they’re cleaning out his room—we’re learning about him through Pamela finding his bullets or his books. I’m looking into Render’s life, but I’m also on Carolyn’s side of the courtroom.

Afton Montgomery

The jacket copy calls the book a “whydunit.” How do you feel about that positioning?

Sarah Gerard

Obviously, this is a book occasioned by a horrible crime. It’s being packaged for a marketplace, which is not what I thought about as I was writing. And I’ll admit I’m not somebody who’s uninterested in crime. I am interested, as a lot of people are, in why people commit crimes, from a sociological, psychological, anthropological point of view. What my publisher is contending with is the fear that the general public doesn’t know Carolyn, so Carolyn herself is not a “selling point.” I think they’re hoping to hook readers.

The “why” does provide solace for me. When I started to research this, I already had a sense that Render was going to plead insanity. And I’m an artist, most of my friends are artists, most of us struggle with mental illness to some extent. So, the psychological dimension is interesting to me.

There’s also a stigma around pleading insanity; I was curious about that. I didn’t know for another year and a half that he was claiming it was marijuana-induced psychosis, which at the time seemed absurd to me. Now it seems less absurd.

I still don’t know, with a hundred percent certainty, why this happened, but seeking a “why” gives meaning to an event that otherwise seems totally random and is even more frightening in that regard.

I also think every story worth telling has an unanswerable “why” at the center. Right away everybody who knew Carolyn was asking, “Why this person? She’s a good person. There’s nothing she did to deserve this, so why?” Within twenty-four hours, Render was giving an interview in which he said it wasn’t her fault. So why?

Afton Montgomery

You have this character list in the front of the book—132 people and their relationships to Carolyn, Render, and the case. As you were patchworking together these thousands of hours of conversations, what emerged in the interstitial space? And will you speak to the choice to wedge dialogue from separate interviews together to create “conversations”?

Sarah Gerard

I wanted the community to come together to tell Carolyn’s story and for her to be the focus rather than each of these individual people, although I definitely wanted individual people like Pamela to emerge as characters that were fully fleshed. What started emerging were stories that many people would land on, organically. It became apparent which stories needed to be in the book. Pivotal points in Carolyn’s life. A question that I kept asking people is, “What do you think is important to include in her story? What made Carolyn who she is?”

Afton Montgomery

Lilly Dancyger’s new book, First Love, opens with a piece about the author’s cousin Sabina, who was murdered when she was twenty. Dancyger says, “Portraying a real person on the page is always a subtle violence—reducing their multidimensional humanity, the unknowability of their inherent contradictions and mutable nature, into something flat and digestible. Even the best rendered character on the page is only a fraction as complex as a real person. Doing this to a person who has been murdered . . . feels like [an even] larger injustice. . . . Murder already threatens to eclipse a person.”

Your book seems to respond to this concern with pure volume, combining so many voices on Carolyn that you create something like a roving omniscience.

Sarah Gerard

I was cautioned when I started working on this that she would be too difficult to capture. I had that same concern. She was too complex. I fully acknowledge that there’s so much about her that I will never know and that didn’t end up in the book. Obviously, this is not a complete depiction of the person, and it never could be.

I also didn’t want the responsibility of portraying her by myself. I felt really uncomfortable with that because I was not closest to her. It would even be hard to say who was. Pamela had known Carolyn since Carolyn was six but there were even things that she didn’t know about her. And there were things that Jenny [Schatz, Carolyn’s sister] didn’t know that I ended up learning through these interviews.

I wanted to take some of the responsibility off myself and give it back to Carolyn and also empower the people in her life to tell her story.

Afton Montgomery

Your voice is often the quietest voice in the book. This feels especially relevant when you start talking about Bard, mostly because you relied on the information to speak for itself—you do very, very little explication or analysis. Will you talk about using the arrangement of information to communicate meaning?

Sarah Gerard

I was encouraged by my editor to analyze and explain more. But at a certain point, I thought I didn’t even need to. I mean, the events say it all. Leon [Botstein, the president of Bard College] speaks for himself quite well. I don’t know what I could have added at a certain point when he freely comes out and says these are his beliefs, this is the philosophy of the college.

I didn’t go to Bard, so I can’t speak to what it’s like being a student there, but the students can. I interviewed a lot of current and former students. Some even reached out to me because they heard that I was writing about Bard, and they wanted to talk.

I will say, Bard has a great history of activism on its campus, by its students. One of the benefits of students being encouraged to act like adults and think for themselves is that they end up feeling very free to call out hypocrisy and malfeasance at the school, even if nothing changes.

There’s a lot of history in the Bard literature and Bard archives—available online—documentation about what has gone on there. It was very easy for me to corroborate things that I was hearing in interviews—like, about the sex parties. That’s all written about in The Bard Observer, incredibly.

And Leon is a bloviating narcissist. I listened to dozens of hours of interviews with Leon and found so much that he had written that was kind of shocking. The story wrote itself.

Afton Montgomery

Obviously, the book has a lot about it that’s journalistic. It’s clearly very carefully reported. But I also found it interesting how many moments there are when you seem to take mysticism or astrology or a feeling as seriously as you take factual reporting. This felt, to me, like a move against the misogyny of what we interpret to be real, but also, I wondered if it had anything to do with trying to conjure a world that looked more like Carolyn’s world, because she seemed very interested in astrology and that realm.

Sarah Gerard

She was, and she believed in being able to commune with the dead. As do a lot of her friends. As do I. I’m writing from my own subject position as somebody who believes in mediumship and astrology and the Tarot. A lot of that, too, I was learning about because I wanted to learn about her and understand her. I had always had an interest in mysticism and mediumship. That was part of what attracted me to her and what made me want to write about her.

As a writer, I give myself certain projects because they include a lot that I want to learn about. It’s like signing up to take a class on something. In this case, I was signing up to take a class about Carolyn, and everything that went along with that.

All this studying that I did around mysticism and the occult was a journalistic pursuit, and an intellectual one, and a spiritual pursuit for me—I came to understand myself more spiritually. I considered myself vaguely agnostic—borderline atheist—before I started writing this book. But then I started working on it, and I was like, “No, there’s a very palpable and real spiritual realm that affects, in a material way, our everyday life.”

I agree, it’s misogynistic to say that it’s not real. Intuition is derided as a feminine quality, a feminine knowledge. But I use it all the time as an investigator; intuition is a really quantum knowledge base. Carolyn, obviously, was an adamant feminist and took intuition seriously herself. So, part of that was getting to know her, and part of it was getting to know myself, and where we overlapped.

Afton Montgomery

I tried to map out the book to figure out its overarching structure, and my best understanding is there’s a chronology of Carolyn’s life; there’s a chronology of Render’s life; early on is a thread of the crime, plea deal, and news stories leading up to the trial; and after that first thread wanes, there’s a thread about the trial. There are also a couple of chapters that act as standalone reflections on what it is to write this type of book. How did this woven construction come about?

Sarah Gerard

There are four timelines. There is the murder and the time afterward leading up to the trial. Then there’s the trial itself, which gets woven in with the days leading up to it. Then there’s Carolyn’s life. And then later in the book, Render’s life comes in.

I wanted a lot of things to happen before we even got to the trial, but my editor disagreed with that. She thought the trial was going to keep people reading. They know there’s gonna be a trial because there’s been a murder. They’re not going to want to wait until chapter fifteen to learn more about it. So, I satisfied that urge by writing about the plea offer early, which comes before the trial, and that’s when we learned that he was going to plead marijuana-induced psychosis.

But, like I said, the record of Carolyn’s impact and her friends’ grieving was an important narrative for me, and I wanted to give that a lot of space early in the book, as the thing we’re paying attention to, even more than the trial.

There’s a lot of conversation about how to write about murder. Chapter three, Render’s jailhouse interview, was part of that. We learn about Render’s background but also we discuss how to write about something so horrible in a way that is or isn’t respectful to the person whose life was lost.

The jailhouse interview was horrifying to a lot of people. I am a believer in complexity, and I grieve the loss of complexity in our media every day. And I understand why this reporter went to talk to him: (a) that’s her job, (b) nobody else was, (c) what he said actually ended up being really important in the trial.

But also, I understand Carolyn’s loved ones, including myself, finding this just—“gross” is too simple of a word. I was aghast at the things that he was saying, and the fact that it was reported on so “factually.” There was very little conversation about Carolyn, a lot of misinformation, some serious omissions, and just straight-up lies. That set the standard for all the news that came out afterward.

I think that was why, early on in the book, I wanted to query my own reasons for writing it. How can I add to this conversation in a way that is meaningful to Carolyn and her memory and won’t further exploit it?

Which is not to say that I didn’t, either—I’m open to criticisms of this book. There were certainly people who thought I shouldn’t write it at all, and I respect that perspective because this is ultimately a part of our entertainment industry, and I don’t know that that’s what Carolyn would want—for her suffering to be turned into entertainment. But I know she also wanted to write a memoir. I wanted to tell her life story for that reason.

Afton Montgomery

There’s so much complication—obviously books are much more than entertainment, too.

Sarah Gerard

For people who are reading them seriously, yeah. I think some people do just read books for entertainment. Certainly, people listen to true crime podcasts for entertainment. I know that’s where this book is going to be shelved at a bookstore—in the true crime section. It won’t go in the memoir section. I’m not sure what to do about that or if there’s anything I could have done. Because, again, there would be no occasion to write this book if Carolyn didn’t die and no way to write about her without acknowledging how she died. If I acknowledge how she died, I have to write about that.

Afton Montgomery

When you arrive to the book, your “I” pronoun enters subtly. It happens for the first time in the first twenty pages, but it doesn’t feel like you, Sarah, are really present until the vigil at Wendy’s Subway [an arts organization Carolyn co-founded] when you start a paragraph with, “That’s when I arrived.”

Then, for most chapters, you’re faint, but in the trial, it feels like your “I” self is there much more frequently, especially as the pace of the trial picks up.

Sarah Gerard

I was present for most of the trial, whereas I wasn’t there for a lot of the events in the book, so I had to recreate them through other people’s recollections. I was there at the vigil; I think that was the first time when I was like, “I wish I could capture this moment in amber. Preserve it.”

I think I decided to write this because it seemed really clear to me how to do the research; I knew who to reach out to right away. I had an investigative plan. The first person I reached out to was Pamela; the second was Jim, Carolyn’s father; third was Jenny; fourth was Rachel Valinsky, from Wendy’s Subway. And then I started going to the pre-trial hearings in 2017, and Pamela began coming with me.

A courtroom is a really, really boring place. It’s so quiet. It’s so stuffy. It’s so proper; everyone is so serious. It’s kind of an out-of-body experience. Time drags. You spend twenty minutes talking about one surveillance still. You can’t even hear what’s being said from the stand because there’s no amplification. There was no microphone. It wasn’t until I went back and read the transcripts that I could really pick apart what people were saying.

Every little detail gets looked at from ten different angles. And the burden is on the prosecution, not the defense. They have to establish not only the facts, but also the motive, and prove that there was intent, which in this case was really hard to do, because Render was pleading insanity, and they didn’t have a strong argument for premeditation.

When the defense presents their case, and the prosecution gets to cross-examine their witnesses, that’s when a lot of the interesting stuff ends up coming out. The prosecution goes first in the trial and the defense can use everything the prosecution presented as fact.

Then the defense gets to tell a story about the facts. They don’t have to establish them—they just get to shade what the prosecution introduced.

Then the prosecution comes back and says, “Or maybe it’s like this,” and they get to shade it even more. Maybe that’s why it feels like the book speeds up at that point, because the prosecution’s job early on is kind of the boring, hard one.

As for the “I,” I really didn’t want to be at the center of this story, because I wasn’t closest to Carolyn, and the people who were closest to her could tell her story much better than I could. I wanted her to be the center of her own story.

NONFICTION

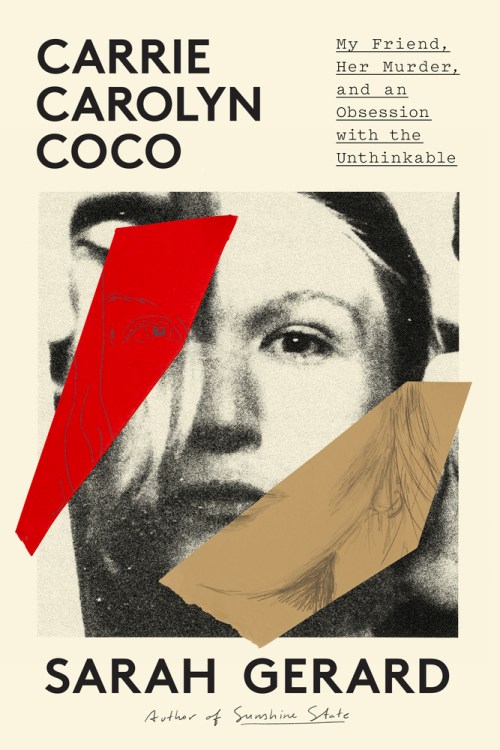

Carrie Carolyn Coco: My Friend, Her Murder, and an Obsession with the Unthinkable

By Sarah Gerard

Zando

Published July 9, 2024

Afton Montgomery was a finalist for the 2023 Harvard Review Chapbook Prize and has recent or forthcoming work in Electric Lit, The Millions, Pleiades, The Common, Passages North, DIAGRAM, Poetry Northwest, Prairie Schooner, Fence, and others. Her work has been supported by fellowships from Centrum, Lighthouse, and Fine Arts Work Center. Formerly an independent bookstore buyer in Denver, Afton calls Colorado home.