Listening—getting out of the way of the story—that is Joan Leegant’s recipe for deliciously complex character-driven stories. Displaced Persons, her third book of fiction, renders family relationships with a keen eye for precise human experiences. The stories explore exile, diaspora, belonging, parenthood, and marriage, often with a sharp sense of humor and an emotional wallop. Winner of the New American Fiction Prize, the book is out now from Milwaukee-based New American Press. I’ve known Leegant since her time as the Hugo House Writer-in-Residence from 2014 to 2016, when we both lived in Seattle; she’s since moved back to Boston and I to Chicago. We corresponded over a Google doc and chatted over Zoom.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Anca L. Szilágyi

An Hour in Paradise, your beautiful debut story collection, released in 2003. Can you comment on any differences you feel between the writing of that first collection and your second, Displaced Persons?

Joan Leegant

Thank you for the compliment.

One of the biggest differences is that, when I was writing the stories that became An Hour in Paradise, I almost never wrote about women; in Displaced Persons, all but 3 of the 14 stories are from a woman’s POV. Men were easier for me to write about when I first began writing fiction (a good thirteen years before I published An Hour in Paradise). Women were simply too close to the bone.

The other difference is that, until I began writing the stories that ultimately made up Displaced Persons, I had written a total of I think two stories in first-person in my life! Suddenly, around the time I initially published “The Baghdadi” in a literary magazine (2012), I was writing in first-person a LOT: women’s voices in first-person. They were gushing out, demanding to be told.

Mainly, I think, it was age. A greater willingness to excavate women’s lives. Displaced Persons has more intimately personal stories—about mental illness, cancer, mothers and fragile sons, aging fathers and adult daughters.

Anca L. Szilágyi

The characters in Displaced Persons feel marvelously complex and inhabit a wide range of experiences: filmmakers trying to break out of Hollywood clichés, a single mother caring for her twenty-something child with severe bipolar disorder in California, an ornery octogenarian connecting with a step-grandson over the history of Jewish gangsters. What is your approach to crafting characters?

Joan Leegant

I don’t think of it as crafting characters so much as letting them emerge, speak, become embodied. I don’t know until I start writing the sentences what or who the story will be about. I try to get out of my own way and let them be who they want to be; to listen and watch for the details that will reveal them to me—a name, a tic, an attitude, a voice. They almost always emerge in the first sentence or two, and they come into existence with the voice; they carry—or are—the voice, and that goes for third-person as well as first-person. If I don’t have the voice, the story will fail.

I was first a lawyer and everything was very head-oriented, very rational and thought-out. It doesn’t work for me to bring that to writing fiction (or essays now, either). I try to hew as closely as I can to the words and sentences as they emerge on the page, to see what they are revealing to me, and then follow them. The writer who articulates this best, for me, is George Saunders in his book A Swim in a Pond in the Rain and a wonderful animated film called “On Story,” which is a piece of a longer interview he did with Syracuse University where he teaches.

Anca L. Szilágyi

Displaced Persons opens with “The Baghdadi,” who came to Israel in 1962 and says “he was not one of those gung-ho Israelis who thought all Jews should live there [….] Only those who had nowhere else to go.” The story goes on to refer to treks across continents, the notion that “Iraqi Jews are always in exile,” and more. What inspired this story and why did you choose to open the collection with it?

Joan Leegant

I did once have to attend a tedious lecture by a visiting writer when I was teaching at Bar-Ilan University in Israel, which is how that story opens. The settings of the university—the outdoor area where the narrator is sitting when the Baghdadi arrives and asks her to call the US embassy for names of doctors, the students milling around watching her, the coffee place where she and the Baghdadi meet—that all came from my memory of that university’s physical spaces. The actual story—their relationship, his history, and the fact that he was talking about himself and his father—all evolved as I wrote the story. I researched the history of the Jews in Baghdad, because he was talking about it in his unique (boastful, wistful, ultimately pained) way, and that needed to be correct. But I didn’t research it until he started to talk about it.

Ultimately, I put this one first because it had received nice recognition (Special Mention in the Pushcart Prize) and because I thought it was a good introduction to the overall voice of the collection, a narration that wasn’t too jarring or fast, and also was a good intro to the concerns of the collection. Other stories had won prizes too, but I thought this was the one that would introduce the reader to the book best. Choosing one over another as the opening story is a leap. Ultimately you have to choose and leap and hope it works.

Anca L. Szilágyi

Mental illness comes up quite movingly in a few of the stories, “Hunters and Gatherers,” “The Book of Splendor,” and “After.” The question of home is one of the collection’s themes. Can you speak to how mental illness is folded into this theme? Feeling at home in one’s own mind, perhaps?

Joan Leegant

When I was assembling the collection, I mostly thought of mental illness as a form of displacement, but it’s all in the same family of things: exile, not being at home in one’s mind, being divided or separated from one’s true self. There’s a line from “After,” when the narrator thinks about visiting the Washington Monument, the Lincoln Memorial, and says: “Maybe tomorrow I’ll take a tour … a free citizen. I could line up with all the other foreign nationals, all of us from alien nations grateful for the new country we’re in.” So, yes, being mentally ill is like living in a foreign country, in alien terrain.

Mental illness allowed me to explore something else in each case: in the case of “Hunters and Gatherers,” it was about a mother’s love for a son, how you’ll do anything to keep that son alive, even lose your marriage.

In “After,” as I alluded to above, it’s about whether one can be forgiven for doing awful things to the people we love, even if/when we couldn’t help it. And “The Book of Splendor” is about how poetry can bring one to dangerous places. I have a special passion for Allen Ginsberg since he was my father’s cousin (family’s literary pedigree and claim to fame!). I met him only once. But I’m interested in the permeable boundary between poetry and sanity/insanity and the permeable boundary between religion and sanity/insanity. That’s why Nathan, the POV character, worried about the Zohar, how if you read mysticism, you can go crazy, even die. Ginsberg was a devotee of Whitman, which is how Whitman’s mystical poetry found its way into the story.

The illness stories all became paths for me to explore and enter into other life issues and emotions.

Anca L. Szilágyi

Much of the narration feels prickly, in a way that delighted me. It opens the door to a sharp humor that feels especially important to the end of “The Innocent”; can we talk about the necessity of humor?

Joan Leegant

I had a great time writing “The Innocent” because it gave me the chance to use jokes, some of which I found online but others I made up to my great pleasure. I also used a bit of humor in “Roots” (Hirschman’s daughter, Wendy, at the end wears earrings in the form of little silverware and his references to his ugly feet as the workhorses of his body have a touch of humor). I write “heavy” stories but I actually greatly appreciate smart humor in almost any form.

The joke at the end of “The Innocent” I actually heard on a plane, as did my character. That story, in fact, became about the necessity of humor for keeping that marriage together: if the narrator’s husband had just given her a little slack, had allowed himself to be generous in his emotions, and hence not had such a stick up his you-know-what, that marriage might have survived. But that would have required him to laugh at her last joke. And that became—essentially, gave me—the ending: his inability to be kind. To get off his high horse and see her as a person who was trying to save them, save their marriage, for the sake of not just their son but for what once might have been good.

Humor of course is baked into Jewish life, at least in some quarters. Baked into the tragic, the terrible. That’s also what my character was trying to do: find and use some humor to cope with what was going on in her failing marriage. Just as her father had done. The joke I made up (and am unduly proud of!) is one where he talks about being in prison and asks, what’s the difference between prison and life in the suburbs? Answer: in prison they actually use the yard. So he was making the best of having gone to prison, which otherwise would be only a source of shame. That’s another way to think about humor in serious fiction: like in Jewish life, it leavens the pain and the tragedy.

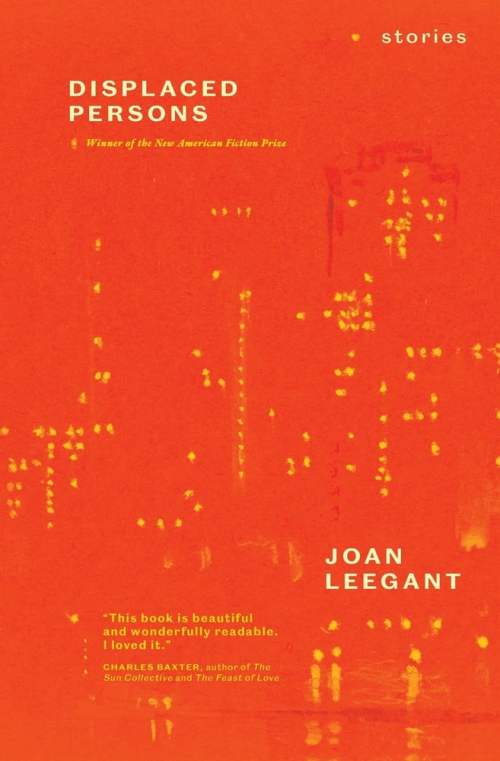

FICTION

Displaced Persons

By Joan Leegant

New American Press

Published June 1, 2024

Anca L. Szilágyi is the author of Daughters of the Air, which Shelf Awareness called “a striking debut from a writer to watch” and Dreams Under Glass, which Buzzfeed Books called “a novel for our modern times.” Her short fiction has appeared in Lilith Magazine, Fairy Tale Review, and Washington City Paper, among other venues. She is working on a collection of food essays, some of which have appeared in Orion Magazine, Los Angeles Review of Books, and The Fiddlehead, and which have been listed as a notable essay in Best American Essays 2023. Originally from Brooklyn, she has lived in Montreal, Seattle, and now Chicago, where she teaches creative writing.