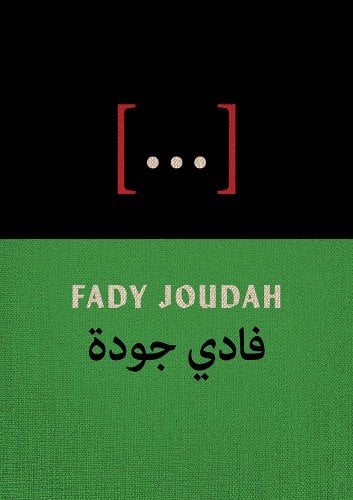

I was deeply affected by artist Alisha Wormsley’s installation “There are Black People in the Future,” with its essential assertion that despite societal actions—and inactions—the systemic violence performed against Black people would never, could never, eliminate their presence and significance in our world. […], the new, exceptionally present, and unforgettable collection by Palestinian-American poet and physician Fady Joudah—emotionally, politically, lyrically, and yes, hopefully—makes the same necessary affirmation: “[T]here will be Gaza after the dark times.”

Even the title of the collection exhibits layers of meaning, both as punctuation and the subject that it is punctuating, underscored by the symbolic representation of the failure of words. What do ellipses mean to you? I use them without thought, almost as much as I do Emily Dickinson’s em dash, both as a way to indicate what I can’t describe and what is missing. I can’t consider them with such innocence again; now I see how each dot can represent an end: of life, of dreams. And yet, in Joudah’s sensitive hands, these ellipses, as much as they indicate silence and the silenced, also render hope that points to a future.

That most of the poems are entitled “[…]” also reflects a blurring accumulation. Naming is a mighty act, but the absence of such perhaps proclaims something equally powerful. Though the titles are literally symbolic, the poems within are not, and within that friction is the poetry, which reframes and refrains unimaginable loss. With bombs exploding through one’s home, rubbling one’s land and very existence, there is no time to pack, no way to grab what you want to preserve, and certainly, no time to title poems. Another effect is an echo of continuation, both of war, and also of resilience, a narrative progression that whispers of and this…and this…and this….

Joudah sets the stakes of this collection in the first poem:

“I write for the future

because my present is demolished.

I fly to the future

to retrieve my demolished present

as a legible past. To see

what isn’t hard to see

in a world that doesn’t.”

Though he writes “I am not your translator.” (his well-regarded works of translation include Maya Abu Al Hayyat’s You Can Be the Last Leaf), Joudah’s poetry—and translations, for that matter—are precise and emotive. I’m also taken with the second person address of this excerpt, in which the speaker can no longer perform the (exhausting) task of tailoring language to make it more palatable for certain audiences:

“Why don’t you denounce

what you ask me to denounce.

We can do it together on the count of three.

Or you should go first”

During my elementary school social studies classes of the last century—post-Vietnam War, pre-Iranian Revolution—there was this underlying sentiment that we were lucky to be living in peacetime. As a child, I accepted this. The worst happening to me then were standard-issue bullies mocking my slightly-accented otherness. Innocent times, to be sure. But once we are adults, once we open our eyes and commit to witnessing, we know there is never true peacetime in our world. When we consider all the internecine wars in our history, present and future, there is no closing punctuation, just continuation, on every continent, in every language. This collection is poetry as gerund: it isn’t past, or passed, but directly in the present moment.

“Dedication” is the longest poem in the book, an entwining of an elegy and list poem, that feels endless, and yet, never-ending, despite the last full stop.

“…To the martyrs who witness

from above, and the living who witness on the ground. To those who

will be killed on the last day of the war. To those who will be killed

on the first day after the war ends. To those who succumb in the

humanitarian window of horror. An hour before the pause, a minute

after. To those who die of a broken heart during and after the war.

To those who gather their families to die together so that no survivor

suffers survival alone. To those who scatter their families so that

they’re not all wiped out from the civil record.”

This is another example of the expansive quality of this urgent collection, which is both deeply personal and painfully open-ended. It’s indicative of Joudah’s poetic prowess that these poems are as immediate as the destruction still facing Palestinians as I write this, and also have a timeless nature. They are both elegiac and a declaration for, and of, a future. “Great joys exhaust me, / small ones bring me to tears.” Joudah writes, which feels like a precise and perfect distillation of our times.

I’ve thought so much about this collection, and how to write about it with meaning and care, given such stakes. Do I even have the right, when those affected most should have their voices elevated instead? I would much rather focus on Joudah’s words than my own.

Yet I also ascribe to the poetry of witness: actively seeing the devastation of the Palestinian people, the ruin of Gaza, is necessary; honestly considering how we may be complicit in others’ pain, inadvertently or not, is necessary. Witnessing is an active verb, not a passive one, and thus we each have a responsibility to participate, to support, to share and especially: “To see // what isn’t hard to see.”

Throughout time—first as an oral tradition—poets have captured what cannot be fully expressed in prose, in ways that comfort, reveal, spark action, and ultimately, bring us into community, which is the only hope civilizations have. The work in […] succeeds as remarkable poetry, and it also tasks readers to remember what ground it arises from: shattered, sorrowful, and sacred.

Let me give Joudah the final words: “[T]here will be Gaza after the dark times.”

POETRY

[…]

By Fady Joudah

Milkweed Editions

March 5, 2024

Mandana Chaffa is founder and editor-in-chief of Nowruz Journal, a periodical of Persian arts and letters and a finalist for the Community of Literary Magazines and Presses’s Best Magazine/Debut; and an editor-at-large at Chicago Review of Books. She serves on the board of the National Book Critics Circle, where she is vice president of the Barrios Book in Translation Prize, and is president of the board of The Flow Chart Foundation. Born in Tehran, Iran, she lives in New York.