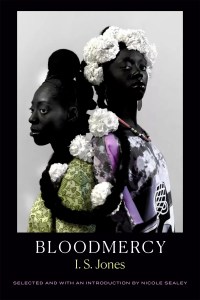

Selected by Nicole Sealey as the winner of the 2025 American Poetry Review/Honickman First Book Prize, I.S. Jones’s Bloodmercy is a blazing debut. Polyvocal and confident, this collection reworks the original biblical story, imagining Cain and Abel as sisters, borne into violence, and Jones’s assured and complex interrogations extend into the dictates of other mythological narratives. These poems upend the narrow patriarchal confines of such narratives, and starkly explore how they shape, repress, and scar. Cain may be marked, but so are we all.

Yet this epic framework is only the starting point of poems that are intimate, bare, embodied, and yes, tender. Though blood is plentiful—as in all origin stories—so too is mercy. At the close of the first poem, “After The Offering Ritual, Cain Carries Abel Home,” Jones writes:

“…And what does mercy look like

between humans? A sister reaching to lift a sister

from the ground. When I say a love that will end us,

I mean ‘mercy’. Remember, I offered you my hand once.

Push me away if you like.”

This is a collection to hold close, a poet to heed.

Mandana Chaffa

Bloodmercy tackles the original origin story with a deeply intimate personal narrative rendered by the line: “Once I was myth, now I am a girl.” What was the first poem that sparked this journey…and did it make it into the final collection?

I.S. Jones

Thank you for this lovely opening question! Anne Sexton, a controversial poet, heavily inspires the line, I’ll be frank to say, as my understanding was she wasn’t a good mother, yet that inspiration only adds to the complexity and the lore.

The answer gets a bit tricky because the first poem I wrote for the book is “Cain” but the oldest poem in the book, and the poem I think really brings together the poems as a book is “Self-Portrait As The Blk Girl Becoming The Beast Everyone Thought She Was.” Though the book is new to the world, his book is seven years old, and so there are still versions of Bloodmercy rattling in my head.

Mandana Chaffa

Changing Cain and Abel to two sisters is endlessly generative, upending what and how we look upon the roles of women, connections of sisters, and the general erasure of women both biblically and societally. None of Adam and Eve’s female children are named in any records, even considering the taboo violence that created the human race after them.

I.S. Jones

Which I’ve always found so fascinating! Canonically, Cain and Abel have two sisters, Aclima and Jumela, with their names changing depending on the culture, yet they are almost never mentioned. I looked into them and thought, in passing, about them if they would make sense in this re-imaging. I ultimately decided not to use them because they felt too one-dimensional. I hope someone takes up the mantle and digs deeper into those girls. As you aptly stated, this subject matter is endlessly generative.

There is a book I found during the production of this book titled “The Women of the Bible” and in it was an encyclopedia of every woman in the Bible. It wasn’t lost on me that many didn’t have a name.

Mandana Chaffa

There’s an intense polyvocality in these pieces that supports—demands—complex close reading, and often, there is a wild shapeshifting within the poems, a confident wrestling with narrative, an embrace of contradictions that serves the collection well. How did the ultimate arc of the book flow and change from conception to completion?

I.S. Jones

Thank you for this generous question. Me from two years ago would have sobbed from gratitude. It was tough and demanding, as any good book is. In the beginning, the most difficult part was differentiating each of the voices—Eve, Cain, and Abel. In workshop, the critique was that it was often unclear who was speaking when. Then I realized the ordering can help with this. I credit “Tetsuo and Youth” by Lupe Fiasco for teaching me how to order a manuscript, as that album has a clear narrative arc both guided by the seasons but also by the central voice’s run towards freedom.

So I did what I often love to do, what I learned (for better or worse) from Kanye West to toss things out and start over. When I reordered the book, I gave both the girls their own section with Eve bisecting each section. “The future bisecting the past” is a concept that governs the book. So the opening poem (if you count that as a section) is Cain. Section two is all Cain with poems flowing into Eve’s perspective. In “Cain In The Peopleless Kingdom,” the poem ends with Cain witnessing the abuse Adam brings upon her mother then transitions the narrative to Eve in the succeeding poem. To integrate Eve into the girls’ sections, I looked to the first four books of The New Testament because it’s the near-same story told from four different perspectives. It was important that the structure of the Bible influenced the book’s orientation.

Section one ends with a poem focused on Abel to segue us into section two—Abel’s section. When we get to section three, this was where I struggled with the book. The first three section—opening, Cain, and then Abel—were clear as I was setting the foreground for the girl’s childhood. By section three, I knew Eve, Abel, and Cain would all be talking throughout but how it would be structured wasn’t yet clear. Then I remembered something: when I was very young, [probably] 12 or 13 when we were still living in New Jersey, my parents effectively separated. My father worked in Milwaukee and we stayed together (my siblings and mother) back in the home we owned at the time. A core memory was my mother telling me how she hoped my father would never come back. It’s terrifying and interesting what children remember. I remember the fighting lessened and without my father in the house, my sister and I had more space to grow. Coming back to this memory, that’s where section three begins.

Mandana Chaffa

“born non-white & woman, call the thing what it is: / hostile uppity neckrolls hips without logic / mean-mugs vengeful at the root /but you’ve only known my mercy”

“Self-Portrait of the Blk Girl Becoming the Beast Everyone Though She Was” whether in Cain’s voice, or an ode to Cain, I’m not entirely sure, is a breathtaking individual manifesto, within a powerful and matriarchal lineage that includes Abel, Lilith, and, of course, Eve: who says elsewhere: I know Death: / it met me at the edge of myself and gave me a new name, then sent me back.” Can we talk about agency, identity(ies), and reinvention?

I.S. Jones

For clarity: Yes, that poem is in Cain’s voice. When it made its way into section three, I thought to make that clear, yet I wanted to trust that the reader could make that connection instinctively. Each of the young women in Bloodmercy (Eve, Cain, Abel, and even Lilith, though she is very briefly mentioned) tells their own stories, engaging in the duality of reinvention and identity. What would be called “reinvention” I see as the readers being gifted a window into their complicated and rich inner lives. Of all the voices, Abel was both the most challenging and exciting because, canonically, she has no voice. No personality. Nothing that rounds out the sum of her life except for being slain by their sibling. The first murder. The first betrayal. In ruminating on this void left by history, Abel as a voice allowed me to do what brought me to writing in the first place–an opportunity to angle myself into a better future. Throughout her girlhood, Abel negotiates the politics of beauty and labor, providing me with the space to explore my own sexuality further, my enduring questions to God, and fraught emotions around blood ties.

Mandana Chaffa

In the Persian language, ‘Baba’ is the tender honorific for father and reading that word in several of these poems had a visceral impact on me, a reminder that including vocabulary specific to the poet—rather than serving to ease readers understanding—creates an authentic and intimate space for connection. Similarly, some of the Yoruba language, though I wouldn’t understand literally, had an outsize effect in how layered the experience of the poems are. Would you talk about those decisions in these pieces?

I.S. Jones

It would be my honor. I love how “Baba” exists in many languages, evoking this very feeling you talk about—a tenderness that comes from looking up at a revered father figure. In my child mind, in some of my oldest memories/daydreams, I figured people in the Old Testament didn’t refer to God as such for its overly formal tone. “Baba” immediately creates a dynamic of a doting father. In these daydreams, God has no face or rather a face so immaculate it would be profane for any human to gaze on him directly. In Yoruba, when we call to God, we say “Baba God.” That sense of intimacy was essential to the book because it makes the stakes of the human world more brutal.

Regarding Yoruba, I wanted to add more poems moving between both languages, yet “Juice or Milk” was the most (and only) urgent poem in that regard because it is the oldest myth about myself. I also wrote that poem for my mother. I didn’t speak English for the first five years of my life because, at home, we talked and prayed in Yoruba. All the prayer songs from my childhood are in Yoruba. When writing in a language that isn’t English [chuckles], it’s important to me that I translate in the line as to not scare people away, but also as to not break the momentum building up. There is a deliberate choice not to italicize the non-English words because it sets a precedent about power and importance. I have faith that my readers are curious like me and would only be invigorated by such unusual (read: delightful) choices.

Mandana Chaffa

In “First Sighting,” there was a line I was taken with: “Say it with me: I am no longer ashamed to want.” What a powerful statement, one that I still struggle with even now, whether by dint of culture or gender. And certainly, this debut is a tangible result of wanting, and fulfilling a long-awaited desire.

I.S. Jones

You know, when I held my book for the first time in my career as a writer, I felt complete satisfaction. Proud, yes, but also in awe that my book miraculously looks and feels better than my dreams.

Frankly, I am obsessed with declarations and declarative lines in a poem. For me, to have such a command of language tastes like a piece of the Divine: “I declare it & it is so.” My love for the declaration began with Lorde’s “Poetry Is Not A Luxury”: “The White fathers told us ‘I think, therefore I am.’ The Black Mother within each of us—the poet-–whispers in our dreams: ‘I feel therefore I can be free’.” Desire, if accepted, can be a kind of freedom.

POETRY

POETRY

Bloodmercy

By I.S. Jones

American Poetry Review

Published September 9, 2025

Mandana Chaffa is a writer, editor and critic whose work has appeared in a variety of publications and venues. She is founder and editor of Nowruz Journal and an editor-at-large at Chicago Review of Books. She serves on the boards of Brooklyn Poets, where she is Treasurer; the National Book Critics Circle where she is vice president of the Barrios Book in Translation Prize and co-vice president of Membership; and is also the president of the board of The Flow Chart Foundation. Born in Tehran, Iran, she lives in New York.