Keith S. Wilson’s new book, Games For Children, is unlike any book I have ever read or expect to read. It is rare, certainly, to read a book that delves so deeply into experimental forms, but it is extremely rare to read a book that does so while maintaining a sense of intimacy between the speaker and the reader. Even when we are looking at complex graphs or sentence diagrams we never lose the sense that Keith—or the avatar of Keith that we call the speaker—is speaking directly to us. This is, to me, the poetry of the future.

Keith and I were roommates for one quarter during our time as Stegner Fellows at Stanford. Often I’d walk out of my room and find him at the kitchen table painting with gouache or editing an inDesign file he had spread across his laptop screen and a second monitor. Once I walked out of my room and found him surrounded by eight or nine small Raspberry Pi computers with which, he claimed nonchalantly, he was making a poem.

Jackson Holbert

Where does your interest in visual poems and new forms come from? My sense is that a lot of the time when we’re pushing into new forms, it comes from a feeling that the pre-existing forms are incapable of expressing what needs to be said.

Keith S. Wilson

One of the things about language is that it’s not just a way to express your thoughts but also a way to have them in the first place. The visual poems are a more expansive way of allowing that to happen. When I put this down, is it true? When I put it down and decide it’s not true but it still feels right, what does that mean? And the visual poems are part of a practice of pushing myself, though I do think that a push can be anything. It doesn’t have to be avant garde or experimental. Right now for me, it’s writing narratives. Can I write those? I don’t know. But I want to know what I am capable of, or what language is capable of.

Jackson Holbert

What does something feeling true look like to you?

Keith S. Wilson

One of the reasons that I write about math and science has to do with the primacy of truth. There’s a way in which those areas of study are understood as—and present themselves as—objective. “Here’s what truth is.” Truth has always been more complicated than that. Nothing is true until it’s interpreted and embodied, and as a result of that, I put stuff down on the page, and read it and ask myself: what is it that I’m feeling about this? Because feeling is inextricable from rationality, however much we want to separate them. And so there’s a way that describing what truth is within a poem is actually impossible to answer succinctly. It’s different for every poem and different for every line. Sometimes it’s an emotional thing, where it’s like: Oh! You know, there’s a way that this sounds true, but it’s not actually true of my experience.

And sometimes it’s almost a matter of reaching past truth, or ignoring truth, to say something that expresses incomprehensibility. Love is one of these things that I talk about all the time, in this way. It’s one of the reasons I use math or space to talk about love. I’m doing that in my poem “there aren’t enough idioms about the stars.” Trying to say something that is sort of impossible to grasp and that itself represents a kind of truth. That this is not a thing that can actually be described, or summarized, or proven. Only felt.

Jackson Holbert

You mentioned pushing yourself earlier. Did you find that the visual poems pushed you harder than the traditionally lineated ones?

Keith S. Wilson

I still think love poems are the hardest poems to write. I’m still writing them, and they definitely appear in Games for Children. There are also poems about my dad, who had stomach cancer and was really sick when I was working on my first book, and at that time, I couldn’t bear to write about it. But Games for Children also deals with injustice and structures of power and oppression, and the history of violence. And so going back to the thing I said earlier about incomprehensibility: that’s something that surrounds all those topics. For instance, there’s a way in which it’s very easy and pat to say that you’re anti-violent. But then, when you think about the history of American violence, one of the ways that violence has manifested itself here is in slave insurrection. So what’s the hindsight-is-20/20 solution for how to resolve slavery that wouldn’t have involved any violence? Everything about that topic is incomprehensible. The suffering, the scope, the options, the ramifications. So that’s what these different forms are getting at. They’re different ways of approaching it—new paths to allow something to happen on the page, or in the mind. Maybe there is no one destination. Or the destination is beside the point.

Jackson Holbert

A lot of these visual poems will be unlike any poems readers have encountered. And many of them have no clear beginnings or endings. Do you think of the reader experience while revising these?

Keith S. Wilson

Douglas Kearney has a quote from Mess and Mess and, where someone asked him “what is the difference between poetry and rhetoric?” And he writes “one holds an argument as snake handlers might a diamond back. The rhetorician grips securely the scaly collar, ensuring the serpent doesn’t bite. The poet, however, may find purchase further down the spine, leaving the viper free to writhe, to strike.” One of the things I really love about that quote is the idea of the poem as a less-tethered viper—there’s a power in that, and also a danger. That’s what the visual poem is to me. And that is some of what is happening when I allow the reader—or force them—to figure out what order they’re gonna read a poem in.

When you look at a painting, there’s no way for the visual artist who created it to know for sure what part you’ll look at first, or how long you’ll spend on that painting. There are things that they can do to try to guide your eye, and those things exist in my poetry as well. But part of the power of a visual work is in the viewer or the reader making those choices for themselves.

Jackson Holbert

Can you talk a bit about what you see as the connection between poetry and games? The book is called Game is for Children, and we see forms of games coming up in the book in many forms.

Keith S. Wilson

Games bring two sets of associations for me. One of them is the second part of the title of Games for Children. I’ve always been very interested in wonder—it’s something that drives me to write about science and love: experiencing the vastness of those things is comparable to being a child experiencing anything. I’ve seen my nieces fall, or be scared by something sudden, and seeing their faces try to comprehend it—it’s heartbreaking. Whatever that feeling is, the book is about that. But also, games are representations of systems. Many of the visual poems in my book are approaching systems of oppression, of violence, of politics.

The way that those two intersect—wonder and systemic oppression—on one hand feels like a contradiction, but also it’s just… true. There’s a poem in the book called “Apotheosis” where I recall something my dad told me when I was a teenager: that one of his friends in Cincinnati, when he was a teenager himself, was riding in a car and leaned out of the window with a baseball bat and hit a friend with it. As a joke. And it killed that other kid. That’s another thing about being young. Obviously not all children are violent but that mindset of doing something that is just incredibly dangerous, incredibly short-sighted. It’s an aspect of play. Sometimes games hurt people. And not always because people broke the rules, but sometimes because they followed them.

Jackson Holbert

I want to talk about your poem “Walmart,” which is centered on a story about a coworker getting injured at work and being forced to sign forms with his bloody hand before he is allowed to go to the hospital. You are the only poet I know who has an active forklift operator’s license, and I know you’ve worked more than your fair share of warehouse and receiving jobs over the years. Obviously those experiences provided you subject matter, but did they change how you thought about poetry?

Keith S. Wilson

When people think of form, they’re almost always thinking of received forms—of sonnets, villanelles. If the idea is that the constrictions or challenges of form heighten the work by being in conversation with the writing itself, I think that true, too, of one’s lived life. That labor, for instance, is a set of formal constrictions.

In my first book, many more poems had to be speculative or personal. Things that you can write without having to do research, because I was working 60 and 70 hours a week at Walmart, or Fedex, or the Amazon warehouse in Hebron, Kentucky. There are poems in this book that involve a lot of research that I could only do once I had jobs that let me overlap my research interests with my teaching. Once I got funding. So essentially, a bunch of time exists in Games for Children that didn’t exist in Fieldnotes on Ordinary Love, and that quite literally changed the shape of the book.

Jackson Holbert

Many of the traditionally lineated poems are about your life, and most of the visual poems are about more abstract things like power structures—do you find that one form fits a certain subject matter better?

Keith S. Wilson

I think one of the reasons might be that thinking of games as systems lends itself to discussions of systems. I think another reason is that while I don’t believe that the only way to read my poems is to first go do a bunch of outside research, it is an option that is available if you want to have a place of purchase—if you want to get a hold of them from another vantage point. You can’t Google my life to find out what I’m talking about in a love poem, so there’s a sense of traditional clarity that is perhaps especially important with those more personal poems.

Jackson Holbert

The last poem in the book contains, in terms of language, only a one word epigraph from a Sappho fragment. Often I think poems aren’t about language, they’re about something else. What that something else is I don’t know. Maybe shapes. How did you come to this poem?

Keith S. Wilson

Poetry as a form has this tradition or allowance for what you might call lyrical ambiguity, or lyrical contradiction, or confusion, or ellipsis. The missingness of direct sense—making leads to these magnificent moments of transcendence. And so, I was thinking about Sappho, whose poetry I love and yet some of what’s happening in her work was not only not intentional, it wasn’t originally happening at all. Because we literally just don’t have all of the pieces. And it’s similar to looking at ancient statues that are missing their arms. If you’re moved, you’re partially moved by the absence. So one of the things I was thinking about when I was writing that poem is what are the ways that poetry is happening through the missingness, through the lack.

Jackson Holbert

Was it always the last poem? A poem without language feels like a very fitting end.

Keith S. Wilson

No, no, … One of the things that’s sort of complicated about the book is that the foundations of it, the “Uncanny” series of poems, was still being written up until the book was nearly done. It’s the final poem of the “Uncanny” series, and it was written, if that’s what you’d call it, after all the others. So in a way, the book was constantly being reimagined. It had a million different forms.

Jackson Holbert

So those “Uncanny” poems were the first visual poems you wrote for the book?

Keith S. Wilson

Well, the first and the last, yeah. The very first one I ever wrote was “Uncanny Emmett Till,” and then it was many, many years before I made an attempt at the second one. Instead, I started experimenting more with other visual pieces. And so for like, 7 or 8 years, it was like sketching a million figure studies to prepare yourself for someone you’re going to meet some day.

Jackson Holbert

One of the things I was struck by is how many poems here are made from common objects. Venn diagrams, switch diagrams, gerrymandered maps. Part of the power of the book for me is that after we read it we go out into the world seeing these things as fodder for poems.

Keith S. Wilson

I think of poetry as both a way to write and a way to read. You can read anything that way. Words, but also—as you say—common objects. Signs and symbols. I wrote the gerrymander/sentence diagram poem, “Gerrymander for a Black Sentence,” because a version of gerrymandering happens with language all the time as well. And that’s a more insidious, sometimes even more invisible thing. So when I look at a sentence diagram, which has all these associations with prescriptive grammar—of describing but also regulating language—I can read it as gerrymandered. Anyone can. The question is, if you see it happening, how do you express what you’ve seen?

Jackson Holbert

That seems connected to the poems not necessarily getting at answers.

Keith S. Wilson

Yeah. One of the challenges with writing the notes section was figuring out what I wanted to say and how much I wanted to say it. The notes section was a very late inclusion. I was thinking: if you see an electrical diagram and don’t know what that is, how would you even begin to investigate it? One thing that’s really interesting about that electrical diagram poem—it’s called “Field Switch”—is that my dad’s a retired electrical engineer, and I was giving him his copy and he immediately pointed out the ground symbol in that poem. Of course, an electrical engineer understanding the ground symbol is not evidence that people will immediately get that set of references. But it’s interesting how legibility is never universal.

Jackson Holbert

Well, thank you for that. Any predictions for the new year?

Keith S. Wilson

I’ve been thinking that one of the responses to AI that I hope to see is people just being more interested in live music, and bands. Like in the 90s there was this brief moment where swing music came back. I think we need that again. Turning some music on and being like: Ska is back!

POETRY

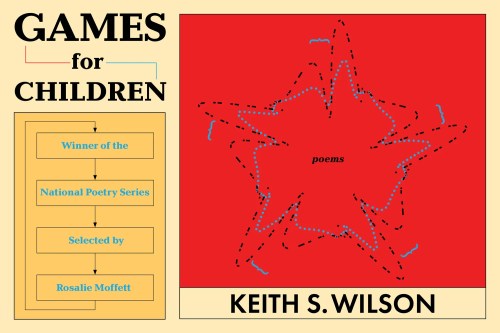

Games for Children

By Keith S. Wilson

Milkweed Editions

Published August 26, 2025

Jackson Holbert's was born and raised in eastern Washington. His book, Winter Stranger, won Milkweed Editions' Max Ritvo Prize. His work has appeared in The Nation, Poetry, and Narrative. He is currently a Jones Lecturer at Stanford and lives in Oakland.