In many large communities, some members are welcomed and others shunned. But how are these fraught decisions made in oppressed communities, and more importantly, who gets to make them?

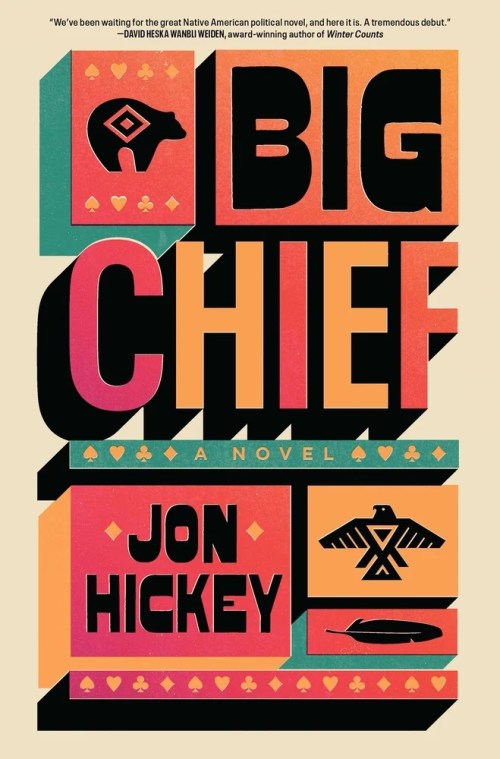

The question of who belongs and who polices belonging is a central point in John Hickey’s debut novel, a political drama that takes place on a tribal reservation in the north woods of Wisconsin. Big Chief showcases Hickey’s intimate understanding of electoral politics, small town corruption, and contested authority within the Anishinaabe reservation of Passage Rouge. Hickey’s protagonist is Mitch Caddo, an orphaned son of Passage Rouge, who has become the embattled top advisor to tribal president Mack Beck during the final days of Mack’s unpopular reign. On top of that, Mack happens to be chief executive of the Golden Eagle Casino, “the economic center of the reservation that rakes in $25 million a year, home of the loosest slots in the state.” But he is also Mitch’s childhood friend and the son of one of the most respected white men in Passage Rouge, Joe Beck, who is a father figure to Mitch. In the final days of the election campaign, Mitch’s complicated relationship with Mack—who once protected him during fights with other neighborhood kids and who vouched for him over the years—is put to the test as his friend discards the legal and ethical norms of his office.

On Feast Day, otherwise known as Thanksgiving, Mitch accompanies Mack to distribute checks and turkey dinners to wary constituents in the parking lot outside the administrative offices of the Government Center. Under Mack’s orders, tribal police officers headed by his enforcer, Bobby Lone Eagle, disperse the picketers that gathered to protest the administration. It is not the last we see of the protesters; their numbers gradually increase over the course of the novel until a high stakes standoff on the floor of the casino in the penultimate scene. Demonstrators—led by local elders and supporters of Mack’s opponent in the election, “Indian country celebrity” Gloria Hawkins—pose a highly visible threat to Mack’s floundering campaign. The protesters camp out in the Government Center parking lot and burn ceremonial cedar wood. They refuse to be intimidated by the tribal president’s “ursine” demeanor or his chosen mode of transportation, the aptly named Big Chief, a “Ford Super Duty F-350” with an “ice white exterior,” “bulletproof tinted glass,” and vanity plates that read “BGCHIEF.”

We follow Mitch over the five days leading up to the election as he strives to please his mercurial, hard-charging boss, whose rash decisions frequently counteract Mitch’s best advice. Hickey doesn’t shy away from backstory, delivered in Mitch’s casual, irreverent voice. Some chapters felt a bit bogged down by exposition. We learn that Mitch’s father left at a young age, his mother died in a tragic car crash, and he went on to graduate from Cornell Law before urging Mack to run for office. From there, Mitch struggles to negotiate the tension between satisfying Mack and honoring the memory of his mother, who once believed strongly in Mack’s rival, Gloria. When Mitch and his boss receive a tip from the Department of Justice, Mitch must decide if he is going to let Mack’s foster father and the tribal general counsel, Joe, take the fall for rampant corruption within their ranks. Meanwhile, memories of an old fling are stirred up by the appearance of Layla Beck, Mack’s sister. Layla emerges as a key supporter of Gloria Hawkins and an effective rabble rouser. The protesters’ ranks swell while Mitch forces himself to carry out the tribal president’s dirty business. Mack uses the DOJ tip to subjugate the tribal council and banish Gloria and Joe, leading to a showdown with a massive crowd of demonstrators that feels something like a reservation version of a constitutional crisis.

Hickey’s plot is busy, and the setting is engrossing enough to distract us from the fact that Mitch is a bit of a wet blanket. Mitch seems quite comfortable languishing in the shadow of the throne. “I’m meant to be invisible,” he explains, “to blend in.” The problem is that this innate passivity, which Mitch himself might attribute to a fear of rejection, prevents him from stepping into the spotlight of the novel, something we might expect from its protagonist. His lack of confidence can be frustrating. Plenty of great books feature passive protagonists, from Nick in The Great Gatsby to Truman Capote’s unnamed narrator in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, who make up for their mousy qualities with memorable voices. Mitch Caddo, however, rarely speaks up. He asserts himself only when he can safely get away with it, and even toward the end of the novel, after finally turning against Mack’s depraved administration, he does so through strategic inaction, rather than forcefully claiming the moral high ground. After finally revolting against the doomed regime, Mitch still cannot seem to find his voice; instead, he wanders alone through the dark, snowbound forest, risking death from hypothermia. A rare opportunity for clarity and decisiveness is cast off in favor of listlessness, stasis, and the inertia of ice.

Yet Hickey has found a rich topic in exploring questions of indigenous authenticity. His characters are exiled, accepted and rejected, loved and forgotten. Mack seems to especially relish his power to banish residents of the reservation, a shrewd and ruthless way of forcing undesirables out of the community and off the voter rolls. The strategy effectively chips away at Gloria’s voting base while creating a culture of fear among the populace. But by doing so, Mack fancies himself the self-appointed arbiter of belonging in a community that is defined largely by its indigenous identity and history of resistance against the United States. One of Mack’s defining traits is his contempt for his white father, while Mitch himself is referred to pejoratively as a “half breed” who attended a fancy law school and who, unlike Mack, nobody expects to stick around for very long. In this way, Mack and Mitch represent opposing camps on the reservation, the insider and outsider respectively, and Mack’s re-election campaign becomes the battleground for a power struggle between the two poles.

The setting of the Passage Rouge reservation in the relatively isolated forests of northern Wisconsin is a strong point. Through a gradual accumulation of detail, Hickey creates a realistic stage that he sets with locations like the Golden Eagle Casino and Government Center, Lake Ogema, and Peace Pipe Road. The setting entices us closer to Mitch and Mack and Joe and Layla and all their neighbors, many of whom grew up on the “rez” and know it intimately. Ironically, Hickey’s readers are invited into Passage Rouge more readily than some of its longest inhabitants, given Mack’s unilateral banishment of political opponents and neighbors whom he deems a threat.

Ultimately, I struggled to extract a moral lesson or thesis from the transgressions of Mack Beck and his lackeys. They are accused by a growing throng of protesters of an “abuse of power,” a reference to their exiling of political opponents, and also to embezzlement, or at least the failure to stop embezzlement from occurring. No small crimes, these, and yet these actions are never framed for us in a larger context. I was as surprised as the narrator to discover in the novel’s epilogue that Mitch’s most corrupt conspirators are made to serve minimal prison time before returning to live on the “rez” after their release, implying that the scales of justice have failed to check the real heavyweights behind the Mack Beck administration. It’s all interesting fodder for this particular political moment; this is a story about an unapologetically partisan leader who routinely bends or breaks the law in order to enact what he sees as a mandate to deliver a harsh set of populist policies that sow chaos during a particularly vulnerable moment.

At one point, as Mack Beck strides onto the busy floor of the Golden Eagle casino, Hickey likens the aura of power he exudes to a “low frequency rumble.” In the present political moment, this feels familiar. Perhaps we have all grown so accustomed to the sound that we don’t even notice it anymore.

FICTION

by Jon Hickey

Simon & Schuster

Published on April 8, 2025

Max Gray is a writer and artist of many stripes. His essays and criticism have appeared in the Chicago Review of Books and The Rumpus. His science fiction story "The Simulation" appeared in Amazing Stories' Best of 2024 anthology. You can hear him perform and learn more about him at maxwgray.wixsite.com/max-gray