Gabriel Fried’s upcoming collection of poetry, No Small Thing (Four Way Books), is a tour of identities, interpersonal expectations, and the blend of internal and external perceptions that shape an individual. Across three sections, “Older Boys,” “Schoolyard Evangel,” and “Stay, Illusion,” readers meet speakers who question their own identities and the norms that shape said identities while also reconceptualizing images they have of themselves. Boys become men; men become pregnant women; adults question–and sometimes follow–the spiritual guidance of children.

At every stage, No Small Thing is a joy, even–especially–when certain poems appear removed from joy.

Below, Fried and I discuss the double helix of identity, re-weaving the coerced un-queering that societies enacts on individuals, and the ability form has to help readers unmask identities placed on them.

RS Deeren:

From the first poem, “Hart,” there is a double helix of identities. The contrapuntal form gives readers a speaker who is both one and two voices, who shares their understanding of a gendered identity. Sometimes there is overlap, other times the voices diverge to almost give two separate speakers. How does this poem set a tone for the rest of the collection?

Gabriel Fried:

“Hart” is one of the older poems in the collection, but I always knew it would come first because of the elements you describe: that “both one and twoness” of the voice(s), which feels so essential to my poem-writing these days.

I think of the voices in “Hart” as recounting a concurrence or confluence of existences, which ripple around a single, shared embodiment. It’s completely reasonable to use the terms “identity” and “understanding” when asking about the poem, but I think of its provenance as something more inchoate, which its grown-up speaker only feels compelled to describe because that shimmering (nonbinary) existence is dulled, retracted maybe, by external forces.

The theorist Kathryn Bond Stockton writes about children being, in effect, de-queered as they grow up—not always with the express cauterizing objective of heteronormativity, but nonetheless with that effect. Our world so carelessly and non-consensually unweaves the double-helix you describe, and I think this poem writes obliquely into that coercion. I have spent decades trying to mend myself from that unweaving, to bring those threads back together where they belong. I think (hope) the poems in this book get at that in a variety of respects, especially in the book’s first section.

RS Deeren:

Much of the work here highlights moments of splitting and rejoining—of voices, perspectives, past or imagined versions of speakers. “Before the Sermon,” “The Time We Broke into the Church to Pray,” and “One Is” are examples of this. How do you see this collection navigating the complications and even contradictions of one’s identity?

Gabriel Fried:

We commonly hear people say that they are “spiritual, but not religious” as a way of proclaiming—what?—an earnest, soul-searching, and humble relationship to the great mysteries without attaching oneself to oppressive institutions or dogma. By now, it’s something we maybe roll our eyes at, even if we (I) have probably said it ourselves at some point. If I am being honest, though, I think there is a downplaying of devotion that comes with the disclaimer “but not religious,” one that doesn’t really match the gravitas of my own spiritual experiences—especially those in childhood, in which I felt in profound harmony with unseen forces that I perceived to be operating, in an almost gnostic way, behind the curtain of the “real world.” I grew up in a Jewish family that, post-Holocaust, was moving, generally speaking, further and further from religious practice, let alone faith; and have spent a life mostly around people who are at least ambivalent about faith—and in many cases hostile toward it.

The poems you name gently push back against that antipathy, which I don’t exactly share, and write into my abiding enthrallment with the divine. My poem’s speakers often feel to me like congregants in search of a congregation.

RS Deeren:

These poems are a masterclass in the power of individual lines and the multiple understandings a reader can draw from the act of repetition. This comes through in part by the nature of a triolet, but also in your use of the form. “Poolside Superhero Triolet” and “Parenting Triolet” come to mind. Can you speak about the work that goes into discovering and using these lines? Is there a joy or satisfaction that comes from these “ah-ha” moments?

Gabriel Fried:

Oh, there is so much joy—elation!—in the form, even when the poem written in it isn’t joyful. Triolets are the product of what I think of as ‘serious play,’ an engagement with lines and sentences that ask for and withstand scrutiny. They have competing qualities of rigidity and flexibility, part marble statue and part origami. The initial use of the refraining lines needs to be convincing and essential on its own, but those lines also need to either allow for repurposing or for being used in a way that justifies their out-and-out repetition. (I remember Renee Flemming, the great soprano, talking about how, in Baroque opera, in which there is a lot of musical and lyrical repetition, a singer can’t just repeat the lines as rote the way you might in a pop song; there has to be a reason the line is repeated, whether it’s a doubling-down or a reinvention. A triolet is the same way. If you’re merely fulfilling the obligations of the form, it’s probably going to end up feeling over-starched.)

I am drawn to refraining forms, too, for reasons related to your first question about identity and embodiment: they provide opportunities to transform our expectations for language, which is such a big component of how we conceive of and describe ourselves.

Triolets have saved me in periods when I feel stalled or don’t have much time to write. Generally, I can write one in one sitting, though I end up tossing a lot of them in the trash bin. The form is so compact and conspicuous that, as soon as the poem is complete, it’s usually pretty clear whether or not it is a keeper.

RS Deeren:

A theme running through this collection is one of “becoming.” The speaker in “The Majesty of Piero Della Francesca” —an assimilated male Jew gazing on the Madonna del Parto—is granted transcendence for a moment. The parent speakers in “Testimony” wonder who their son is and what will become of him. The boy speaker in “Origin Story” becomes a storyteller telling men “the one true lie about” himself. Is the notion of becoming more like a mask—a man becoming a pregnant woman? Or is this becoming more of an unmasking?

Gabriel Fried:

To me it feels like an unmasking, or a yearning to be able to unmask or to be a version of oneself that others don’t (or won’t) see. But that includes the Jewish man who becomes a pregnant woman seeking the blessing of the pregnant Virgin. It may sound like donning of a mask or costume, when it is the removal of a costume that one hasn’t chosen or consented to wear. That’s why Piero’s painting is so perfect: are the tent folds opening or closing? Is the Virgin’s dress coming off or going on? Living in that moment is somehow both ephemeral and endless.

RS Deeren:

There is an enjoyable bluntness to these poems which brings an earnest sense of humor to non-humorous topics. “The Mole” highlights this, where boys contemplating, potentially causing, the death of an animal are interrupted by the speaker imagining their adult lives as middle managers. “Unrhymed Sonnet by the Atheist Grandfather of the Schoolyard Evangel” is another solid example. Regarding craft, do these moments of humor come early in the drafting process, or is there an uncovering later on? Also, what role do you see humor playing in this collection?

Gabriel Fried:

My poems’ speakers often have a certain sincerity, and one person’s sincerity can be humorous to others. I don’t think of the speakers of the poems in this book as trying to be funny—but the corners of my mouth definitely curl up sometimes when I read certain poems aloud.

I’ve always written poems to find connection. Sometimes that connection comes in feeling out how what we think we know about ourselves isn’t completely congruent with what we don’t, in fact, permit ourselves to know. There is an underlying humor in that discrepancy, I think.

RS Deeren:

The power of faith looms over these poems and plays into themes of gendered, spiritual, sexual, and ethnic identity, especially in the second section of the collection, “Schoolyard Evangel.” Poems such as “Questions About an Atheist” center speakers who want faith to be the single answer to every question, even when so many of these poems offer more questions about faith—either religious, in oneself, or in one’s community. As a poet, how interested are you in finding answers versus presenting questions?

Gabriel Fried:

As a poet, I only ever intend to ask questions, but sometimes, especially when one writes in form, the poems provide answers, like sparks generated by rubbing sticks together. Also, since many of the poems in that second section fall squarely into the realm of persona poetry, it sometimes happens that, even if I am not intent on finding answers, some of their speakers may be. I think the challenge, in those cases, is to suggest the unease that I think must exist beneath the certainty of thinking in absolutes. How might the form of a poem help convey what quavers beneath the confident veneer of a speaker who thinks he has all the answers?

RS Deeren:

Twice in this collection you give an epigraph to other poets, Jenn Gihvan and Lucie Brock-Broido, with the latter engraved at the start of the last section, “Stay, Illusion.” How do you see your work in conversation with these two?

Gabriel Fried:

Lucie Brock-Broido’s eaffect on me has been so profound. I have been trying to write about it elsewhere, and everything I describe about the impact she had on me feels insufficient. That final section of the book is dedicated to her, inhabited by her, and in conversation with her.

You mentioned earlier the line from “Origin Story”—the “one true lie.” Lucie taught me that, in effect, one’s truth needn’t be strictly autobiographical—that one’s psychic, spiritual, and/or imaginative history is just as viable a source when it comes to telling one’s story. Lucie was, I think, a self-made entity, a living work of Baroque art who kept herself, metaphorically, behind velvet ropes—and yet she never seemed to me to abandon her places or people of origin. She was both ethereal and earthy, costumed and authentic. More than anyone else, she gave me permission (explicit and tacit) to both be myself as a writer and create the self I needed to be.

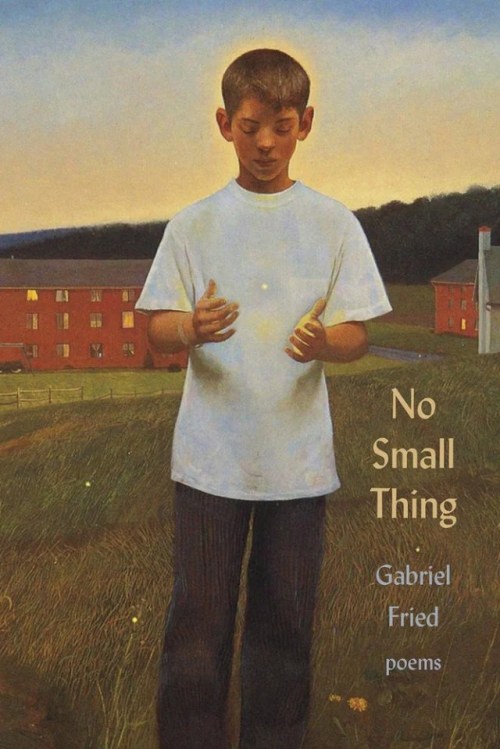

POETRY

No Small Thing

By Gabriel Fried

Four Way Books

Published March 15, 2025

RS Deeren’s debut collection of stories, Enough to Lose (Wayne State University Press 2023 is a 2024 Michigan Notable Book. He earned his MFA from Columbia College Chicago and PhD from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. He is an assistant professor of creative writing at Austin Peay State University in Clarksville, Tennessee, where he is the fiction editor of Zone 3 Press. Before pursuing writing, he worked in the rural Thumb Region of Michigan as a line cook, a landscaper, a bank teller, and a lumberjack. Find him at www.rsdeeren.com and on BlueSky @rsdeeren.bsky.social.

Wonderful ♥️