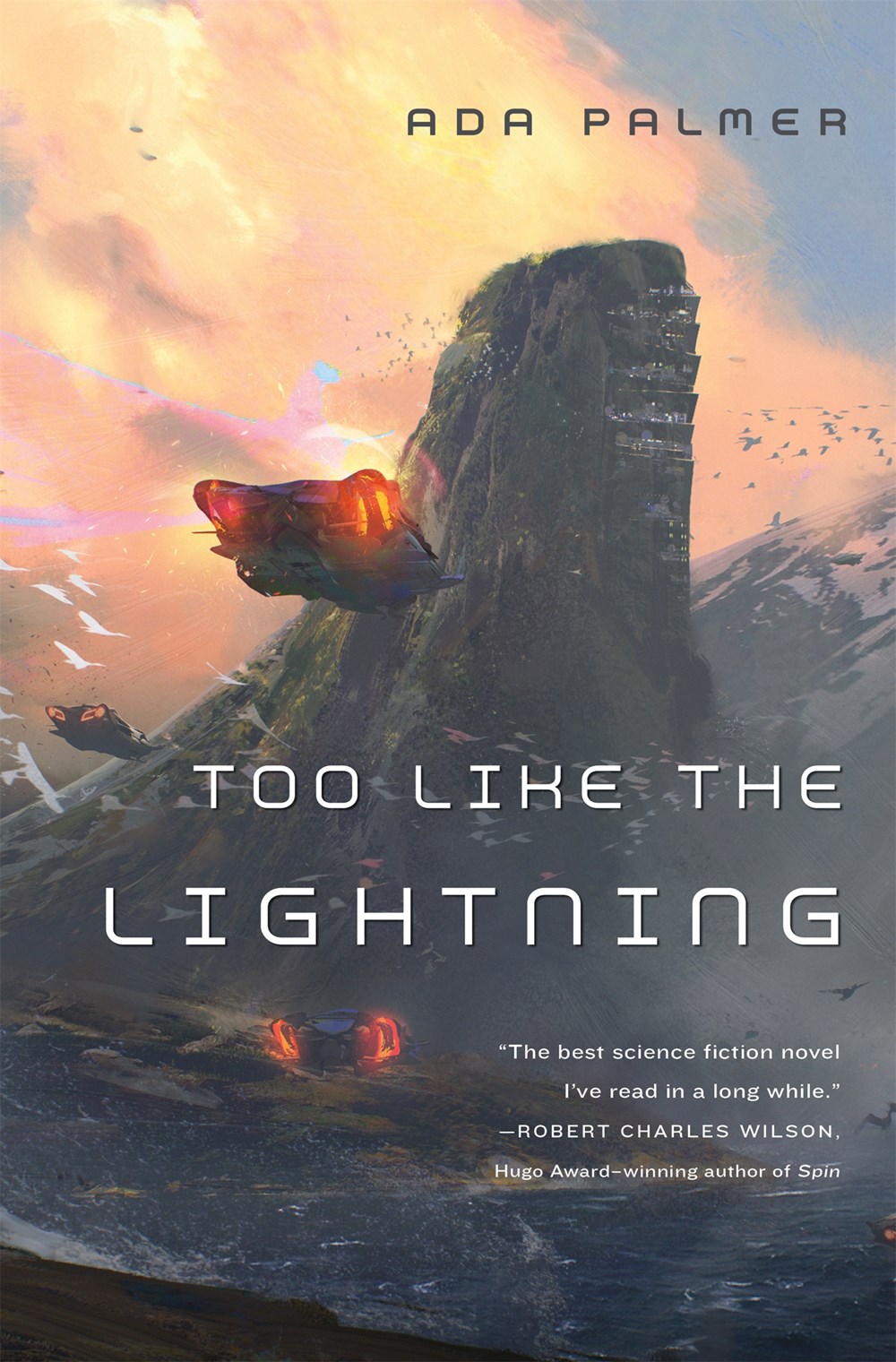

What happens when a University of Chicago history professor writes science fiction? Apparently, you get an ambitious, sprawling, four-book series written in the vernacular of the Enlightenment. Ada Palmer’s debut, Too Like the Lightning, set in the 25th-century world of Terra Ignota (Latin for “land unknown”), is so chock-full of philosophy, sociology, and technology, you could create an entire semester’s syllabus out of it.

What happens when a University of Chicago history professor writes science fiction? Apparently, you get an ambitious, sprawling, four-book series written in the vernacular of the Enlightenment. Ada Palmer’s debut, Too Like the Lightning, set in the 25th-century world of Terra Ignota (Latin for “land unknown”), is so chock-full of philosophy, sociology, and technology, you could create an entire semester’s syllabus out of it.

Mycroft Tanner—a convict sentenced to a life of public servitude—narrates the collapse of Terra Ignota’s political system in a voice reminiscent of Dante and Candide. Throughout the novel, the “Reader” interjects his or her own opinions, questioning Mycroft’s version of the story, and sometimes additional narrators provide the Reader with a new perspective. Shifting points of view and breaking the fourth wall could have easily led to a fractured reading experience, but Palmer weaves the narrative in such a way that the structural and stylistic flourishes are more exciting than they are jarring.

If you, like the “Reader,” experience impatience during the novel’s first 100 pages, you wouldn’t be alone. Palmer pumps the brakes on worldbuilding and jumps straight into the political situation, with only a hint or two of far-future strangeness: nuclear families have been replaced by ‘bashes’; countries have been replaced by ‘Hives’; flying cars can travel the globe in hours; and a secret list of the most powerful people on the planet, the ‘Seven-Ten list’, has been stolen.

The story hinges on the extraordinary abilities of Bridger, a young boy who can make objects and drawings come to life. Though Mycroft originally appears to be the protagonist, it is Bridger who controls the fate of Terra Ignota, while Mycroft is simply his chronicler. “I am the window through which you watch the coming storm,” Mycroft says. “He is the lighting.”

Mycroft’s determination to protect Bridger and his family soon collides with the mystery of the stolen Seven-Ten list. Eventually, the truth behind Mycroft’s crimes come to light, and the surprises keep coming until the very end. But don’t expect a conclusion on the last page: the story will continue in the second book in the Terra Ignota series this December, Seven Surrenders.

One aspect of Too Like the Lightning that is emerging in our own century is the way Palmer has structured the gender roles of Terra Ignota. “They” has become the universal pronoun, gender specifications are all but banned, and everyone wears neutral clothing: wraps and shawls meant to hide sexual characteristics, designed instead to display their chosen factions and allegiances. Organized religion, too, has been sanctioned. This is where Carlyle Foster comes into play, a “sensayer” meant to guide people through their personal explorations of faith.

Too Like the Lightning simultaneously dips its toes in the past and soars into the future, bathing in the imaginative possibilities of technology and society, revealing how even the smallest shifts can destabilize a utopia. Bursting with historical and classical allusions, Palmer’s political and social commentary is as astute as one would expect from a scholar. At times, her prose can be daunting, but the reward—a host of fascinating ideas—makes the book well worth the discipline required to finish it.

FICTION – SCIENCE FICTION

Too Like the Lightning by Ada Palmer

Tor Books

Published May 10, 2016

ISBN 9780765378002

Sara is a writer living and teaching in Chicago. Originally from Texas, Sara relocated to the windy city where she earned her MFA in Fiction Writing from Columbia College. She is the Director of Signature Programs for the writing center StoryStudio Chicago, the Editor-in-Chief of Arcturus magazine, and an Editor-at-Large for the Chicago Review of Books and the Southern Review of Books. She is currently working on a collection of short stories and a novel. You can follow her on twitter and Instagram @sncutaia

First, it’s not at all clear how flying cars make nations unnecessary. The point with nations is not how fast they take you somewhere, but having someplace to go to. So the fictional science part doesn’t really make any sense to me.

Second, the society reminds me of Veronica Roth’s Divergent series. Roth imagines high school as the world and vice versa, with the friendly kids, the churchy kids, the snarky kids and the nerdy kids versus the cool kids. This novel is written by a professor, so it seems to me to be the university as the world. The different Hives are different faculties, different academic disciplines (discipline also meaning rules, or law!) The Utopians are the natural sciences who get the big research contracts and have bunches of money although very little personality. The Mitsubish are the business school, also identified with the Japanese/Chinese/Indians who own lots of things, especially land and buildings. The Masons are the law school, complete with Latin. The Cousins are the school of medicine/nursing, social work, clinical psychology, divinity, anything service oriented and touchy feely. The Europeans are the humanities, The Brillists are the quantitative social sciences, experimental and social psychology, the kind of anthropology that does statistical test of hypotheses. (These are the most unpopular and the least attractive Hive, of course.) The Humanists are the performing arts and athletics department. The Hiveless seem to be the undergraduates. The Heads of the Hives are the Deans, a point hammered home by the way they don’t actually seem to do any administrative work.

Three, the narration is the requisite high literary style. It is ostentatiously modeled on eighteenth century prose styles, ostensibly to reflect the future society’s concern with seventeenth century Enlightenment ideals. It makes much play with how it restores old fashioned notions of gender, using “he” and “she” to line up with stereotypes about what is masculine and feminine. We the reader occasionally interjects directions, criticisms and threats to the narrator, in an old fashioned argot using thee and thou and thy and the gender neutral “they.” The reader also briefly comments

as “A9.” In neither case has the author given us any back story, and very little characterization either. We have bit parts, so far. The narrator is unreliable, reporting to us that there are real Gods in the form of young people with genuinely miraculous powers, though they are not The God. Since the narrator seems to have nefarious motives and the existence of these Divinities drives huge conflicts in the political world, it is possible as of the end of volume one that he’s lying about the miraculous powers of one to cause a war, while the others’ powers are alleged as a means to prevent war.

Four, there is also maybe a giant murder conspiracy which might be aimed at preventing war. And there is a deep laid plot for a serial killer too. Despite these crime novel elements, the author doesn’t seem to have much clue about using crime for insight into society, or about using crime to raise questions about justice. And she especially doesn’t seem to know much about keeping the mystery reader’s interest by providing the aesthetic satisfaction of a good puzzle played out fairly.

Fifth, it’s all Chiefs, no Indians. Everyone is a major world figure and they all know each other. It’s true that the Deans of even a large university know each other. But even a university novel could have ordinary people for ordinary readers to relate too. I was never emotionally engaged.

Sixth, much of the time is spent hinting at some of the deep philosophical issues raised by the Enlightenment in period pastiche style. This is all written elegantly. By the end, the narrator is insisting that the key issue is the question of whether there is a Providence, and Its nature. The conceit of the novel is that Enlightenment rejection of religion has led to the formal disavowal, nay, illegalization of God talk. The clergy is even commanded to offer all religious thinking on trial basis! The basic notion appears to be that religion is necessarily human and the artificial regime must inevitably fall as oppression to the spirit. But maybe that’s the criminal narrator’s scheme? I’m not altogether clear on why religion as supernatural promise of goodies, as systems of political control, as primitive attempts at medicine, as meat redistribution are ignored if the topic is somehow religion. The political issues dear to Enlightenment thinkers are wholly ignored. All the Deans are like Kings and Divine Right is the prevailing philosophy. One of the key political principles is the notion that majority rule causes war. It’s not clear how this is related to anything real world. Maybe some very non-Enlightenment pluralist twaddle where transient pluralities keep the state weak?